We Have Built the Infrastructure for Flexibility.

But The Market Has Barely Used It.

At six o’clock on a winter weekday, Britain behaves with remarkable consistency. Kettles boil, ovens hum, heat pumps work hardest, and demand rises sharply, just as it always has. What makes this moment interesting is not the behaviour itself, but the fact that the electricity system now understands it: in half-hourly detail, across millions of homes, with prices that could, in theory, reflect the strain. For the first time, the technical foundations exist for households to see when electricity is scarce or abundant and to respond accordingly. And yet, despite all this new capability, the daily rhythm of domestic electricity use has barely changed.

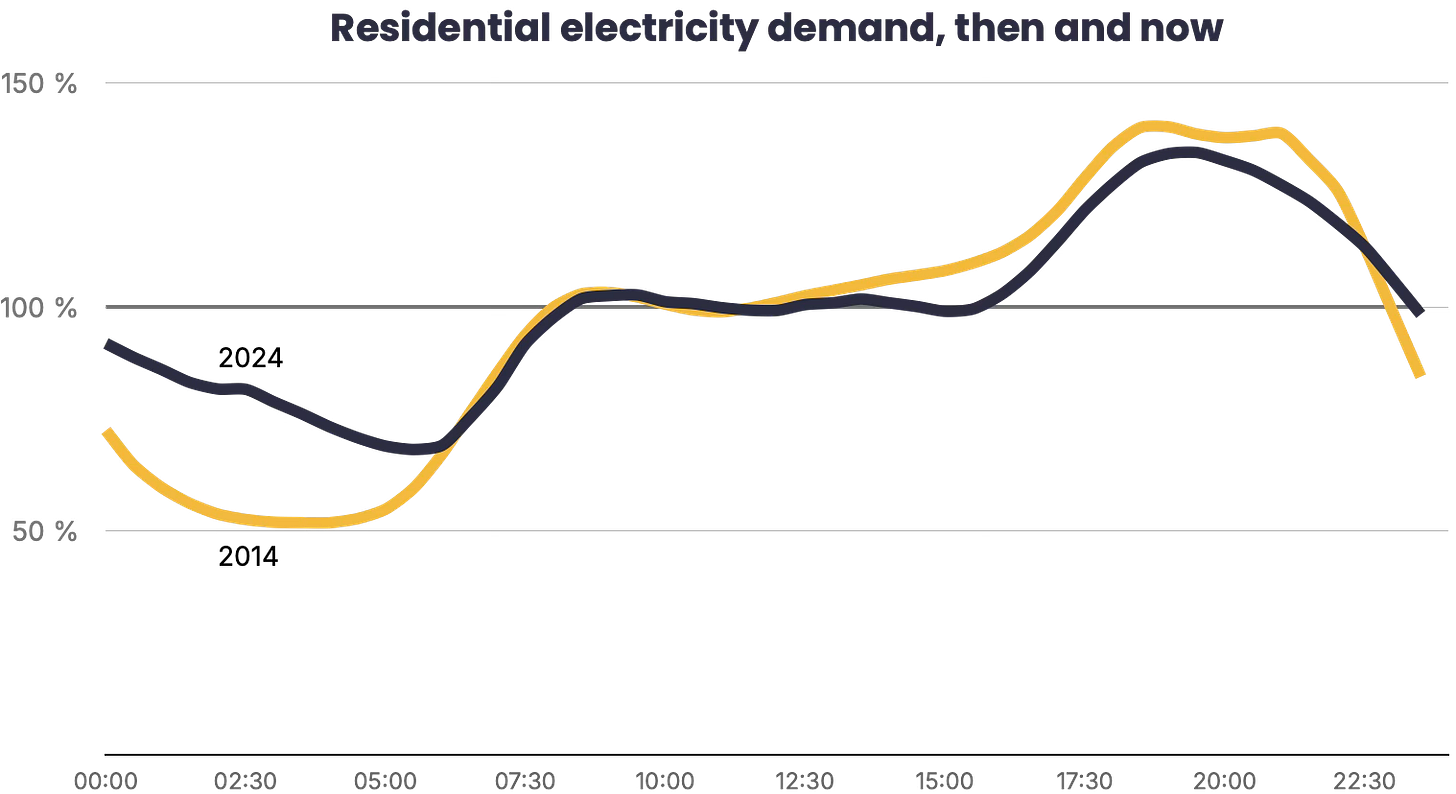

If you compare an average weekday residential load profile from years ago with one from today, the two lines almost sit on top of each other. The defining feature of the day, the evening peak, remains stubbornly intact, rising and falling with the same predictability it always did. The chart below plots the shape of household demand before (2014) and after (2024) the spread of smart meters and flexible tariffs. Whatever progress has been made behind the scenes, it has not yet translated into meaningful behavioural change at scale.

We have built the infrastructure to enable change, but behaviour has barely moved.

That tension sits at the heart of the flexibility debate. Over the past decade, the electricity system itself has changed profoundly. Smart meters are now widespread, half-hourly consumption data is available at scale, and mandatory half-hourly settlement is finally arriving for domestic customers. From a system design perspective, this is not incremental progress but a foundational shift. Without this infrastructure, flexible pricing is impossible; with it, a far richer set of options becomes feasible, from simple time-of-use tariffs to prices that move with real system conditions. On paper, at least, the UK has done the hard part.

Look across the retail market today and flexibility appears to be everywhere. There are tariffs that make electricity cheaper overnight, propositions tailored to electric vehicles or electric heating, and dynamic products that track wholesale prices. Alongside these sit a growing ecosystem of campaigns and add-ons offering free electricity, points, or bill credits in return for shifting demand. Participation is clearly rising, and by the usual metrics this looks like progress. Recent industry-wide analysis has captured this pattern clearly: rapid growth in flexible tariffs and add-ons, alongside a persistent reluctance to expose households to strong or genuinely dynamic price signals. LCP Delta’s recent Beyond Tariffs work reflects this dynamic well. But most of these offers share an important characteristic. They change prices when electricity is cheaper, but rarely explain why, and they rarely allow those prices to move enough to matter. Rates are often fixed for long stretches, differences are smoothed, and volatility is deliberately softened to avoid surprising customers.

From the system’s point of view, that softness matters. Weak signals do not reshape habits, and habits are what define peak demand. The assumption underpinning much of the flexibility narrative is that better information and smarter tariffs will naturally lead to better behaviour.

In practice, households do not respond to elegant market design. They respond to pressure.

Behaviour changes when costs become visible, material, and avoidable, not simply when they are labelled more accurately.

Electric vehicles expose this gap more clearly than any other technology. For many households, buying an EV is the first time energy costs feel both large and flexible at the same time. Petrol is expensive, and you feel it every time you fill up. Charging at home can be much cheaper, but only if timing changes. Suddenly, attention pays. The car becomes an asset that can be moved in time, rather than a fixed demand that simply happens when it happens.

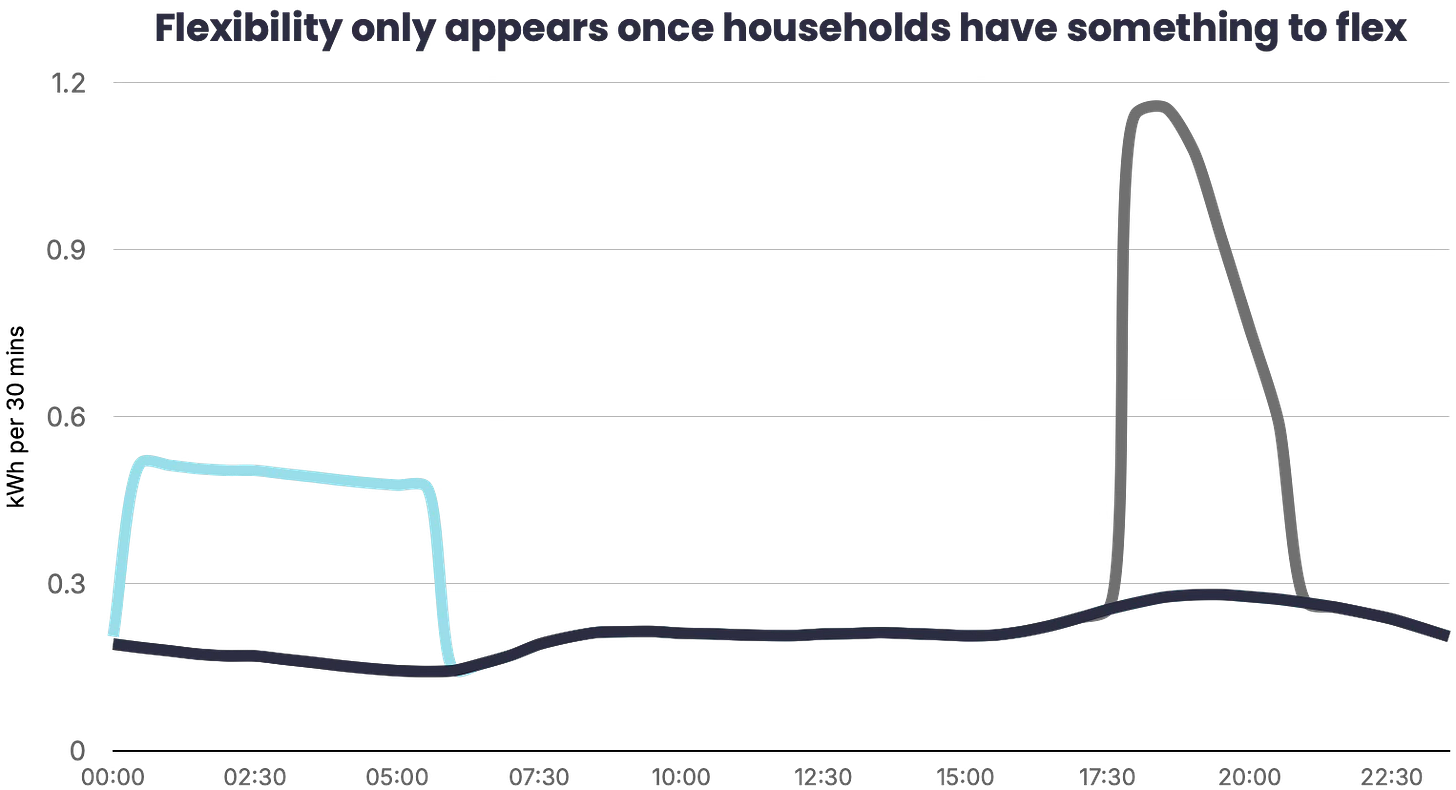

The chart below makes this difference tangible. In a household without an EV, the evening peak dominates the load profile. Add an EV without coordination and that peak often worsens, as charging piles on top of existing demand. Introduce smart charging, however, and something finally shifts: demand moves into the night and the shape of the day begins to change.

The price signal existed in all three cases. It only mattered once there was something behind the meter that could actually respond.

With that in mind, much of today’s flexibility marketing starts to make sense. Free electricity on a Sunday afternoon sounds generous and feels valuable, but unless a household can store it or route it into a meaningful load, the savings are trivial. A dishwasher cycle shifted by a few hours saves pennies.

Most people do not reorganise their lives to save pennies.

It is the petrol station problem all over again: driving out of your way to save a couple of pence a litre feels rational until you do the maths. The effort is real; the reward is not. These offers raise awareness and signal intent, but they rarely reshape daily routines in a durable way.

If flexibility is meant to change demand at scale, it has to make a noticeable difference. That does not mean throwing households into unmanaged volatility, but it does mean being honest about scarcity and abundance and letting price differences do real work. If shifting demand saves pennies, people will not learn; if it saves pounds, they will. Flat tariffs offer no feedback at all, while simple day-night tariffs are blunt instruments inherited from an earlier system. Even many smart tariffs stop short of reflecting why prices move or of allowing those movements to matter.

At this point it is tempting to ask why suppliers do not push harder. Part of the answer lies in trust. The past few years have brought price shocks, supplier failures, and opaque bills, teaching many households that risk tends to flow downhill. Against that backdrop, asking customers to accept variable pricing, share granular data, or hand over control of assets is a significant leap. Suppliers respond rationally by capping prices, bounding downside risk, and making automation optional. Add-ons work precisely because they do not require belief. They are reversible, contained, and psychologically safe, but that safety comes at a cost: signals are softened and outcomes remain shallow.

None of this means residential flexibility is a bad idea. It means we have made it possible without making it meaningful. The tools exist, the assets are arriving, and the infrastructure is largely in place, but weak incentives and low trust have combined to keep behaviour close to where it started. The first chart shows the outcome; and the second shows the exception. Until flexible assets become widespread, or price signals are allowed to matter, the system should not expect households alone to reshape demand.

This is not a failure, but it is a warning. If household flexibility is going to move from experiment to infrastructure, consumers will need tariffs whose logic is clear and whose automation works quietly in the background. Suppliers will need to prioritise trust over cleverness, even if that means taking on more risk themselves. Policymakers will need to recognise that infrastructure is necessary but not sufficient, and that defaults, transparency, and protection will determine whether flexibility scales or stalls.

Flexibility will only really arrive when it becomes boring, when homes quietly optimise themselves and households stop thinking about energy altogether. At six o’clock on a winter weekday, Britain still behaves the same way. Whether that finally changes will depend less on technology, and more on whether the system is willing to let flexibility actually matter.